On Universal Long Term Care

Where Are We Now

In 2020, the number of people age 65 and older was about 16.6% of the population. By 2050, that proportion will rise to around 23.2% and continue to increase as time passes. According to AARP in a 2017 report, the proportion of people who turn 65 who will require long term supports and services at some point during the remainder of their lives is 52%. These figures make it clear that the issue of long term care will have heightened salience as the 21st century progresses.

The Cases for it

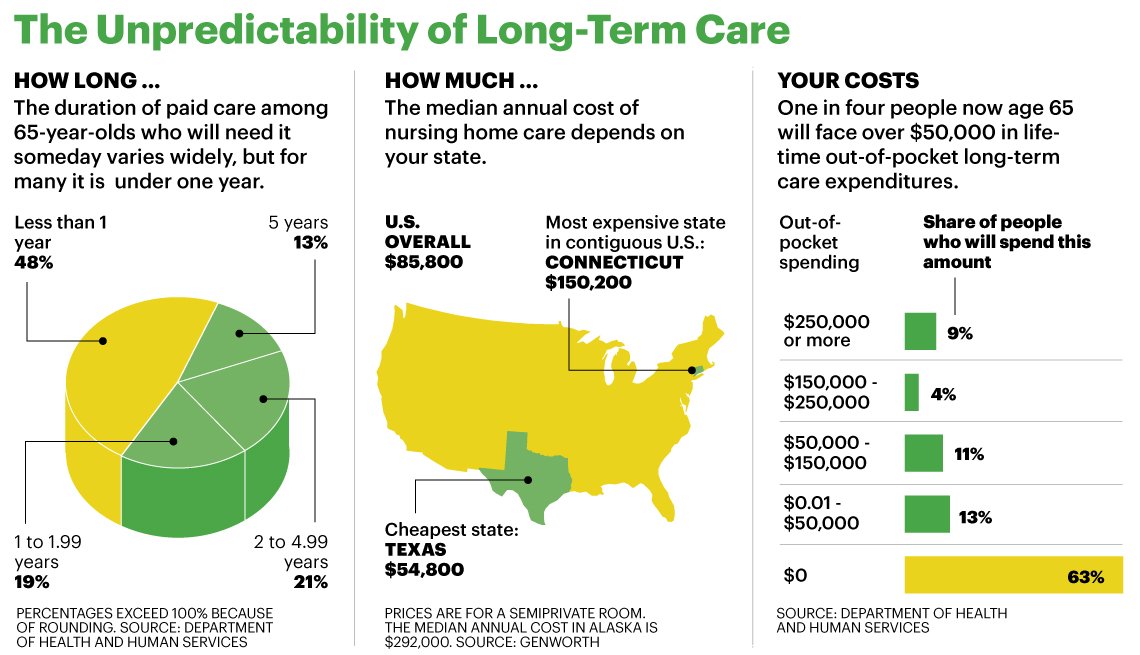

The aforementioned report finds that the average amount of time that people need long term care is 2 years. The breakdown reveals that the required duration of services can vary a lot. Almost half of the population who needs long term care doesn’t need it for more than a year, but a whopping 13% need it for at least 5 years.

Furthermore, as seen in the figure above, many have to pay exorbitant amounts of money. So much for some that their nearly their entire wealth may have to be wiped out to finance long term care.

It Burdens Medicaid

In FY 2019, Medicaid paid out 129.8 billion USD on long term supports and services expenditures. This amounted to nearly a third of all Medicaid expenditures. Medicaid represented 41.36% of all national health expenditures in FY 2019 for the following National Health Expenditures Account (NHEA) data from CMS:

- Home Health Care

- Total Nursing Care Facilities and Continuing Care Retirement Communities

- Other Health, Residential, and Personal Care Expenditures

It’s important to note that Medicare pays for short durations of care post-hospitalization. Thus, the total for long term supports and services paid out by Medicaid is greater than this. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that this proportion was in 2013. The CBO found in 2016 that the expected increase from that year to 2026 in total Medicaid Long Term Supports & Services (LTSS) spending would increase by 38%. The fiscal solvency of Medicaid depends on us adequately addressing long term care.

The Private Market is Dismal

In the above figure, you can see that only 8% of all LTSS expenditures were handled by private insurance. Most people who cannot access Medicaid must exhaust their assets to qualify for assistance, impoverishing middle class seniors. In 2018, the average premium for a private Long Term Care Insurance (LTCI) plan was $2,169 annually. This number increases considerably with age. The size of the market has been shrinking too; a 2016 report by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners found that the LTCI market has been contracting precipitously. This means that beneficiaries get worse benefits at a higher cost as time goes on. To compound this issue, benefits are usually time bound; consumers have to tell insurance firms in advance what their expected duration of care will be. This is preposterous and an impossible question to accurately determine.

Voluntary Schemes Would Lead to A Death Spiral

The actuarial firm Milliman composed a report that serves as an exacting indictment on voluntary private LTCI. The premiums under this scheme would be too high for most people, so only those who have a high expectation to need services would buy plans, driving premiums up even more. This adverse selection would destroy the market completely.

Options

There are a myriad of parameters that we can adjust in designing a universal LTCI program.

Benefit Kick-In

Three primary models exist for benefit timing :

- Front-end

- Back-end

- Comprehensive

The front-end model involves the immediate payment of the benefit as soon as it’s requested or after some short period of time. The benefit is then paid out for a fixed term and terminates when the term has been exhausted. The back-end model has some exclusion period where by the beneficiary must finance expenditures out of pocket. If they’re still paying for care after the exclusion period, they receive the benefit indefinitely as long as it’s needed. The positive aspect of a front-end benefit is that it shields households against acute income shocks. However, it does nothing to sufficiently ameliorate the financial burden of beneficiaries who require LTSS the most. By contrast, the back-end benefit will do far less for the 48% of households who require LTSS for a year or less. However, it would do a superb job at protecting households who have a beneficiary that requires LTSS for a long time from large loss of income. A comprehensive benefit would have a small or non-existent exclusion period like the front-end model, but have the lifetime coverage of the back-end model. It’s the most costly of the three models.

Benefit Structure

The benefit payout can take numerous forms. These include:

- Fee-for-service payments to a institutional provider

- Capitated payments

- Service reimbursement up to a specified cap

- Flat cash benefit

LTSS has shifted away from institutional care, which once dominated care arrangements. A majority of long term care occurs in home and community settings now. For this reason, the first option has lost some relevance. Home and Community Based Care Services (HCBS) has also been found to reduce overall cost. A 1999 publication in JAMA backs this up. A 2017 study also found that hiking waiver spending by $1000 per enrollee was associated with an 8-14% reduction in long term nursing home admission. There is some evidence that non-institutional settings can also reduce total LTSS spending as well as this 2009 study suggests. Furthermore, HCBS allows for more flexibility for patients. Service reimbursement and a pure cash benefit are ideal forms for the current environment of increasing reliance on HCBS.

Benefit Adjustments & Generosity

LTCI designs typically include interest compounding. Typical numbers for these are 3% and 5% annual benefit adjustment. The trade-off here is between increased benefit amounts and higher premiums. There can also be a lifetime maximum payout imposed as well. Finally, there is the consideration of the entitlement structure. Do we want it open-ended, capped, or as a discretionary spending item? Open ended would ensure that benefits will always rise in accordance to beneficiary need, but comes with the concern of adding another structural spigot in the federal budget. A capped benefit would address the concerns of budget hawks and others worried about the deficit as a predefined budget is agreed upon over a long time horizon in this paradigm. An optional mechanism can be implemented in the capped model that allows for periodic review every so often. Here, tax payers can choose whether or not they want to pay for greater benefits and face tax hikes commensurate with the benefit increase.

The Proposal

I propose a back-end catastrophic, social insurance LTCI model that pays a flat cash stipend to beneficiaries. Because the level at which expenses become catastrophic varies by income level, the exclusion period would vary with income level. Here, an exclusion serves the same function a deductible would for other insurance. The exclusion periods are as follows:

- 12 months for people with lifetime incomes in the bottom two income deciles

- 24 months for people with lifetime incomes in the middle income quintile

- 36 months for people with lifetime incomes in the fourth quintile

- 48 months for people with lifetime incomes in the top quintile

Lifetime income would be based on where it was at when the person was 65 or whenever they became disabled if the beneficiary is a disabled person. The eligibility criteria would be anyone who is eligible for Medicare and people under 65 who are disabled. Those who’ve met the impairment thresholds in HIPPA would be eligible to withdraw after the exclusion period. The initial benefit would be set at $115/day sent weekly. It would be annually indexed to inflation and vary based on regional price parity to ensure that folks in certain regions aren’t over or under compensated. The insurance program would be a distinct entitlement under the Social Security Administration. To ensure fiscal sustainability, the program will be phased in over 10 years and be eligible for workers who’ve had at least 40 quarters of work experience after the proposal is enacted into law.

Private Market Reforms

The creation of such a catastrophic benefit would make private LTCI products more viable for both insurers and insurance beneficiaries. This plan considers four pillars of private market reforms

- Reducing product complexity

- Reforming private LTCI regulation

- Reducing marketing costs for firms

- Repurposing existing private LTCI tax subsidies

This package of private market reforms is necessary to create a healthy ecosystem of front-end insurance products to cover the exclusion period people will face, especially those who are middle and higher income who will face a longer exclusion period.

Financing

There are a few options for financing

- Value Added Tax (VAT)

- A surcharge on the Medicare portion of FICA

- A per household head tax

There will also be savings realized in the form of reduced Medicaid expenditures. In our current paradigm of taxation, I recommend the option of a surcharge on top of the Medicare portion of FICA. The rate will be set at the level that allows the program to fully support itself and be actuarially sound for 75 years. There will be periodic reviews every 7 years to ensure that adjustments to premiums can be made if necessary. To address concerns about lower income people paying extra FICA, the premium surcharge could exempt poverty wages at the cost of increase the rate for everyone else. Using the DYNASIM model, I find that an approximately 1% charge levied on Medicare covered income would be sufficient to fund this program initially.

Answering Possible Criticism

Some may dislike that I opted for a catastrophic back-end benefit rather than a comprehensive front-end benefit. The justification for this is that long-term care isn’t cheap and if we’re to help people, the most support should go to those with the least resources and highest needs over others. The Dutch for example pay a 9.65% tax on their wages to finance their comprehensive care. We can provide care for those who need it with much lower tax than that. Other may take issue with the duration of the roll out and the eligibility stipulations. This again is a trade off of sustainability vs generosity. The work history requirements were built in along with the mandates on the premium tax level to ensure solvency. Given the state of our two other entitlements for the elderly and disabled, its imperative any future social insurance is created in a mindful way to ensure the fiscal health of those programs. Furthermore, many lower income can access Medicaid LTSS, so the initial transition isn’t as bad when this is accounted for.

Conclusion

This proposal will lower out of pocket costs families face and lower overall Medicaid spending and reinvigorate the private LTCI market to create effective full coverage for all Americans. This proposal will take time to be fully implemented, so Medicaid LTSS will still remain important in the interim. Regardless, this is an affordable proposal that gives financial relief to families and will also serve to compensate the countless number of Americans working as unpaid help for their relatives and friends. We can’t afford to wait any longer as the most fiscally irresponsible choice is to do nothing.